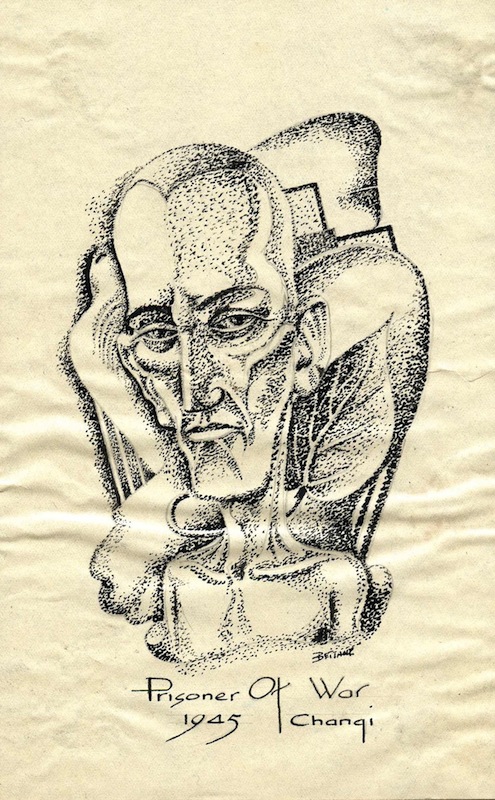

Prisoners of War 1945 – Changi

“As you looked at them, the flesh dropped off their bones, the light of youth from their eyes, the life from their faces. Boys of twenty became suddenly, in physique and expression, old men – shrunken and desperate. ”

“As you looked at them, the flesh dropped off their bones, the light of youth from their eyes, the life from their faces. Boys of twenty became suddenly, in physique and expression, old men – shrunken and desperate. ”

“Our doctors urged us, with good humour and resignation, to do as little as possible each day because the calorific content of our full ration was – they had discovered – only sufficient to enable one to breathe. If one moved or worked then, if pre – war medical standards were to be believed, we must all surely die”.

“The amount of work done by the men who now weighed about eight stone instead of their usual eleven or twelve (and who sank to as low as five or six) was remarkable. The heat had no effect on them. They worked without headwear, they wore only G stings, they ate less each day than international pre war scientists had declared to be the amount on which a man could continue to live, and yet they contrive to plug along for ten or twelve hours on end, shifting tons of obstinate tailings in that time.”.

“The prisoner – of – war life for these four years was an object lesson in living together. The three things that could, at any time kill us all off were work, disease and starvation.”

Source: The Naked Island by Russell Braddon; 1955 edition Pan Books Ltd, Pg121, 131, 181, 252

‘When we were reunited with F Force, there was no doubt that we at Changi had been to some degree deprived of necessary nourishment and it showed in our appearance, but the appearance of the survivors from F Force was such that we were absolutely shocked. They all looked like walking cadavers and gave the appearance of skeletons over which a yellowish – green skin, translucent and almost glowing, had been stretched. And these were the healthiest of the survivors. They were in good spirits at having arrived back to the comparative luxury of Changi, and told amazing stories of death and survival in the various camps along the railway.

Huge numbers had succumbed to tropical ulcers, meningitis, dysentery, dengue, malaria, fatal accidents and plain starvation. One of the major killers was cholera, and they told stories of comparatively healthy men contracting the disease and dying within twenty four hours before they eyes of their comrades. In some camps, fires were kept going twenty fours hours a day so that those who died from cholera could be burnt immediately in order to help prevent the spread of the disease.’

Source: You’ll Never Get Off The Island by Keith Wilson; 1989, Pg 89

‘Counting their actual yeas these men are young, mostly around twenty two or so. But in their shrunken physique and haggard bearing they look to be in their fifties or sixties, undernourished and in the poorest health at that.

They cannot hold themselves properly upright. Their walk – if indeed they are able to walk – is shaky and pain-ridden. They talk only when there is a need to do so. Their speech is slow and difficult, the effort too tiring.

Only in their eyes do most of them show defiance and grim, stubborn determination not to give in. In some, though, there is only despair beyond the reach of friends, and defeat that will surely lead only to longed – for release in death.’

‘We are not in disgrace for letting Singapore be captured so easily, as we have feared we might be. Possibly it is now accepted that we were never given a chance to fight properly, never had the weapons and support which we should have had. To that we would add that political interference and ineptitude, coupled with military incompetence at high level in certain places, is a combination which the ordinary soldier cannot overcome. All he can do is fight and die or, as in our case, become a prisoner, while those responsible retire on undeserved pensions.’

Source: One Fourteenth of an Elephant by Ian Denys Peek, 2005, pg 307 -308; 490 (relating to the condition of POW’s on Thai Burma Railway).

Extracts from One Fourteenth of an Elephant by Ian Denys Peek reprinted by permission of Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd. Copyright © Ian Denys Peek 2003

‘Upon entering the prison camp our hosts placed us on a coolie diet, the main item of which was about 16 ounces of milled rice per man per day. The result was the early appearance of beriberi, to be followed about four weeks later by a most distressing skin trouble, particularly around the genitals. The condition was known locally as ‘rice balls’ or ‘Changi balls’ – the medial term was scrotal dermatitis. Very few prisoners escaped this disease; more serious cases became completely bedridden.’

Source: Burnett Clark, ‘Skin Disease Among Prisoners of War in Malaya’, in Lachlan Grant (ed.), The Changi Book, Published by New South in association with the Australian War Memorial, 2015, pg., 237