Manufacture of Plates for Dentures

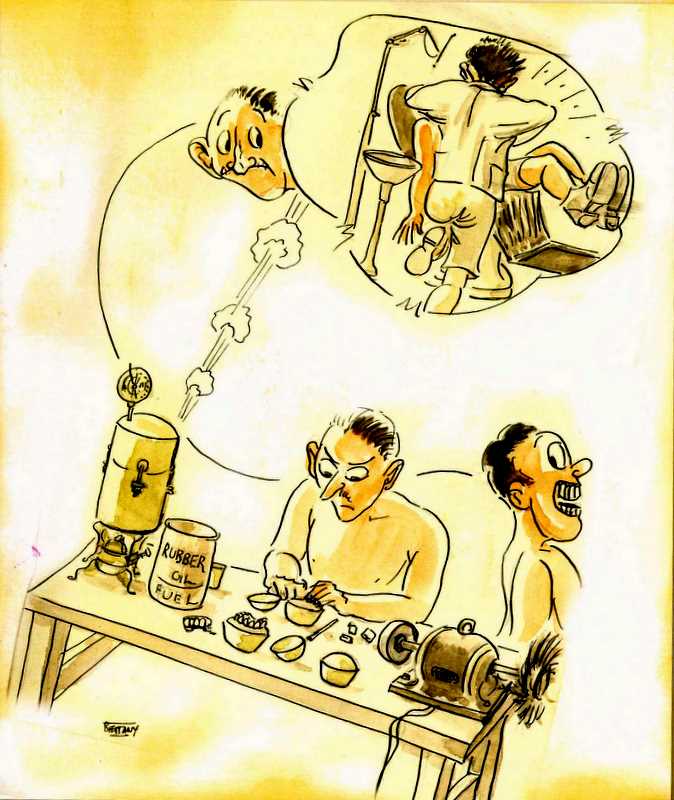

The production of dental rubber for the manufacture of plates for dentures was a success after much experimentation. A fire extinguisher was converted into a still to produce rubber oil from rubber scrap. Dental rubber was treated with this oil to make it pliable. This process can be seen on the above painting, as well as a ‘before and after’ snap shot of a POW without teeth and then with dentures after some manipulation in the dentist chair.

This image of Des Bettany’s artwork has been reproduced with permission from the book ‘Don’t Ever Again Say “It Can’t Be Done”’ published by The Changi Museum, Singapore.

A local GP reports that the Japanese guards also forced the allied dentists to remove a build up of brown tartar on their teeth. He said they would then coated the guards teeth with a ‘protective layer’ of amebic dysentery!! This left them with white teeth but feeling extremely unwell.

‘Most men, at the beginning of their captivity, took one look at the diet of slops and glue and decided that inevitably – and quite soon – all their teeth must fallout. ‘This’, they said, ‘is uncivilised: it is unhygienic – and is most unfortunate,’ and without further ado they resigned themselves to a toothless middle age.

Some idea of the tireless research that went on in the dental department can be gained when on realises that beehives were ruthlessly robbed for wax, crashed planes were stripped for synthetic resin on the cockpit, mosquito cream was stolen for lamps and the cellophane off cigarettes sent by the Red Cross was thriftily collected to be used as a finish for the inside of dentures. To the mechanics and dentists of Changi we owe a great deal.’

Source: Unknown Author, ‘Dental’, in Lachlan Grant (ed.), The Changi Book, Published by New South in association with the Australian War Memorial, 2015, pg. 275, 278

‘On 31st December 1942, Captain Albert Symonds was sent back to Changi …. where he was appointed to be in charge of the camp workshops.

In a community the size of Changi, as a need arose, someone was found with the knowledge or ability to produce what was required … rubber sandals, rope, nails, the list was endless and it included making coffins.

He continued to run the workshops for the duration of his captivity, at the heart of an enterprise which saw prisoners employing remarkable ingenuity to fashion everyday but, nonetheless, vital objects from the most basic materials.

We acquired barrack room lockers … which we cut, shaped and welded into dixies, mugs, baking trays, buckets and pails. We produced toothbrushes and brooms using the same palm fronds that we used for attap. Clogs were mad from motor tyres and from soft rubber wood, and with the latex from the rubber trees we repaired boots and shoes.

When in 1944, the Japanese gave the order that all prisoners were to move to the confines of Changi jail, the workshops were quickly dismantled and relocated and continued to produce a steady stream of much needed equipment, those in the workshops providing much of the labour and ingenuity which went into making the jail more habitable.’

Source: ‘A Cruel Captivity’ by Ellie Taylor, 2018, page 31& 32, Pen & Sword Books Ltd.