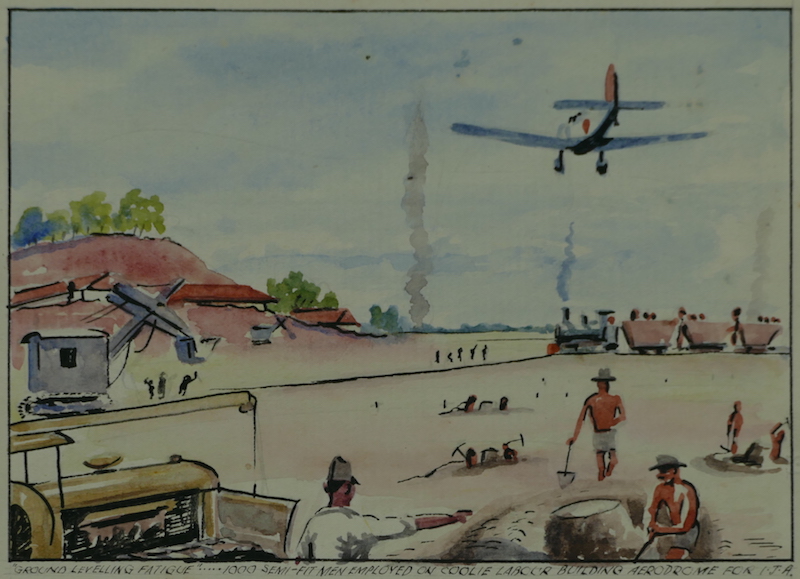

‘Ground Levelling Fatigue’ – Calendar Illustration for August 1946

Ground Levelling Fatigue

‘Ground Levelling Fatigue’…1,000 semi – fit men employed on Coolie labour building Aerodrome for JIA

Thank you: State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library Special Collections where this Calendar is archived

In 2012 fifty million people passed through Changi airport, and it is doubtful many of them gave a moments thought to those who went before them But if they peered into the e past, latter day tourists and business travellers would be surprised to learn that the runway that brought them safely to earth was first tilled, seventy years before, with the blood and sweat of so many prisoners of war.”

Source: The Long Road To Changi, Ewer Peter, 2013, pg 288

To begin with the Ground Levelling Party comprised about 800 men, but it steadily expanded until every fit man was included, together with many who were far from fit. Survivors of the Thailand railway were numbered among them. The work consisted of nothing more or less than shifting hill to swamp.

‘Their bodies almost totally unprotected from the burning heat of the sun and the glare of the pulverised flat of the airstrip, the men toiled at the hillsides, excavating the soil and rock and loading it into hand trucks. These were pushed along the network of narrow-gauge railway lines to the edge of the swamp where the spoil was tipped. When one considers the grossly undernourished condition of the men, most of whom weighed less than two-thirds of their normal weight, and the fact that they were working for between ten and twelve hours a day in gruelling heat, it is truly remarkable what they achieved.’

Source: http://www.abc.net.au/changi/life/concerts.htm

http://ukmamsoba.org/changi.htm

‘The next six months (1944) was a busy time, and a hard one. Though the war news was good, men were in a difficult mood – we could not see the end of hostilities in East Asia. Work on the air strip was extremely arduous and long, rations were at starvation level. Until the surrender our rations consisted of about eight ounzes of rice a day, a little crude palm oil, salt, tea and sometimes an ounze or two of dried fish – this was our entire ration, except for or coarse green leaf vegetables which we grew ourselves. Most people lost from three to seven stone, and the average weight could not have been much over eight stone – each month three or four pounds weight would be lost. Men looked gaunt and haggard. To me it is an amazing thing that they managed to march the four miles to the aerodrome and then work throughout the heat of the day as labourers.’

Source: Down To Bedrock (the diary & secret notes of a Far East prisoner of war Chaplain) by Eric Cordingly, 2013, Pg 137; permission by Louise Reynolds, daughter.

“Nothing, however, could detract from the tedium of the work itself on the Aerodrome. From draining the swamp, clearing mangroves and palms then backfilling it. Digging out the white, gritty, glaring face of that hill, shovelling it into skips, pushing the skips to the other side of the strip and emptying them on to its swampy fringe – gradually filling in and levelling. Then, as a small corner was finished, uprooting all the lines and the sleepers and carrying them to a fresh corner and laying them again. Long lengths of rusty steel lines and the difficult business of lowering them on to the sleepers could result in severed fingers, broken legs and fractured jaws if one end was dropped too soon, springing the whole length into the air.

The amount of work done by the men who now weighed about eight stone instead of their usual eleven or twelve (and who sank to as low as five or six) was remarkable. The heat had no effect on them. They worked without headwear, they wore only G stings, they ate less each day than international pre war scientists had declared to be the amount on which a man could continue to live, and yet they contrive to plug along for ten or twelve hours on end, shifting tons of obstinate tailings in that time.”.

Source: The Naked Island by Russell Braddon; 1955 edition Pan Books Ltd, Pg251 – 252

‘Light, two-foot gauge railways crept across the cleared sections of ground and men shifted hundreds of tons of earth daily by filling skips of one cubic yard capacity and pushing them to a dumping point where the soil was levelled out. The work was constant and was made a great deal harder by the crude tools issued to the workers: shovels and changkols with straight wooden handles and blades fashioned from petrol tins or galvanised iron made the work a great deal harder than it should have been.

Up to date machinery, left undestroyed in Malaya, now made its appearance on the work site. The light railways were replaced by heavy metre gauge, and tracks and caterpillar tractors towing four – and ten – yard – capacity skips moaned across the growing drome. Modern electric shovels and a great steam navvy kept half-a-dozen diesel locomotives pushing long lines of skips heaped with soil to the swamp edges. As each train stopped at a dumping point the ragged workers attacked it with their crude shovels, and within 15 minutes the empty train would be puffing back to the refilling point, leaving the prisoner, sweating and gasping, sitting on the line until the next unloading.

From the beginning of the work the prisoners had comforted themselves … that the war would be over long before the drome was complete, but in June 1944 they watched three fighter aircraft land on the northern arm and the first stage of the work was over.’

Most visitors to Singapore today know Changi as an international aviation hub rather than for its prisoner-of- war connections. But the modern airport that processes tens of millions of travellers each year sits on the foundations of the original aerodrome, built with prisoner-of-war labour in 1944.’

Source: Stan Arneil, ‘The Aerodrome At Changi Point’, in Lachlan Grant (ed.), The Changi Book, Published by New South in association with the Australian War Memorial, 2015, pg., 333 336

‘We were marched off in the morning to work and the airport was made by digging away a hill and filling a swamp. This work was all done by hand, digging and filling small baskets, which were passed along a line of men and then put into a cart and dumped where needed. While working there one day, three Flying Fort planes came over and dropped some bombs on the other end of the airfield, which the Japs were using. This was the first sign in three years of an assurance that our forces were fighting back.’

Source: ‘A Cruel Captivity’ by Ellie Taylor, 2018, page 74, Pen & Sword Books Ltd. , (Words of Able Seaman William Coates Nicholls)