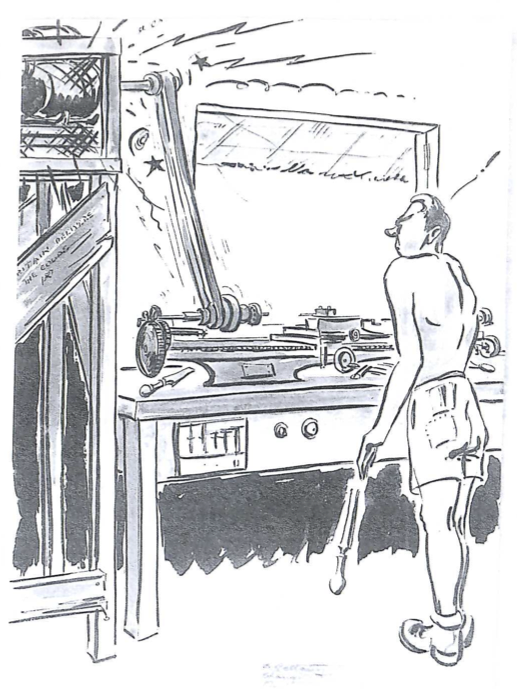

‘Turning Difficulties’ – Limb Factory Changi (1945)

TURNING DIFFICULTIES

Home made lathe for turning up artificial limbs appears to be having some electrical problems.

‘There is not a man who has lost his right arm who cannot write as well with his left and do certain other work as efficiently a before, while to those who have lost a leg this has been an invaluable period of training in the use of his artificial limb. On behalf of the latter a tribute must be paid to the limb factory people who, with practically nothing to start from, managed to create an organisation for the work of which there can be nothing but praise.’

‘In addition to the above there was the regular parade every morning of the men who had lost a leg above the knee. This particular kind of amputation necessitated a longer artificial leg and one which was consequently much more difficult to wear. It was natural that these men should find walking with crutches much easier that using the artificial leg, and the result was that they were inclined to overlook practicing with the latter. To overcome this a parade was held every morning when all these fellows stalked mechanically along the road in front of the depot like so many robots. It was these in particular (to which) the name of the ‘Panzer Division’ was facetiously given (and) which afterwards came to include all those with artificial legs.’

Source: Rex Bucknell, ‘The Panzer Division’, in Lachlan Grant (ed.), The Changi Book, Published by New South in association with the Australian War Memorial, 2015, pg. 156, 158

‘A lathe … was constructed from salvaged head and tailstock, saddle and tool rest. This considerably enlarged workshop scope. Lathe work … consisted of hinges for artificial limbs, manufacture of pieces of woodwind instruments, repair of rice crushers, manufacture of cases and moulds for cricket and baseballs, winding of transformers, and manufacture of baseball bats. The lathe was driven by a one – horsepower motor, the transmission being truck fan belts.’

Source: Unknown Author, ‘The Tinkers of Selarang’, in Lachlan Grant (ed.), The Changi Book, Published by New South in association with the Australian War Memorial, 2015, pg. 189

‘In Changi there was an orthopedic workshop where the prisoners made crutches and artificial limbs out of wood and leather and any other material they could scrounge.’

Source: Down To Bedrock (the diary & secret notes of a Far East prisoner of war Chaplain) by Eric Cordingly, Pg 75; permission by Louis Reynolds, daughter.

‘And another workshop where filing cabinets and rubber trees were wrought into artificial limbs – beautiful pieces of work which their owners (hundreds of amputees from Thailand and Burma), preferred after the war to the products given them by a grateful Government at home. They were light and walked without squeaking and the young craftsmen who made them were happy to modify and modify until the stump of the leg fitted snugly and without chafing into the socket of the artificial limb.’

Source: The Naked Island by Russell Braddon; 1955 edition Pan Books Ltd, Pg 246

‘On 31st December 1942, Captain Albert Symonds was sent back to Changi …. where he was appointed to be in charge of the camp workshops.

In a community the size of Changi, as a need arose, someone was found with the knowledge or ability to produce what was required … rubber sandals, rope, nails, the list was endless and it included making coffins.

He continued to run the workshops for the duration of his captivity, at the heart of an enterprise which saw prisoners employing remarkable ingenuity to fashion everyday but, nonetheless, vital objects from the most basic materials.

We acquired barrack room lockers … which we cut, shaped and welded into dixies, mugs, baking trays, buckets and pails. We produced toothbrushes and brooms using the same palm fronds that we used for attap. Clogs were mad from motor tyres and from soft rubber wood, and with the latex from the rubber trees we repaired boots and shoes.

When in 1944, the Japanese gave the order that all prisoners were to move to the confines of Changi jail, the workshops were quickly dismantled and relocated and continued to produce a steady stream of much needed equipment, those in the workshops providing much of the labour and ingenuity which went into making the jail more habitable.’

Source: ‘A Cruel Captivity’ by Ellie Taylor, 2018, page 31& 32, Pen & Sword Books Ltd.