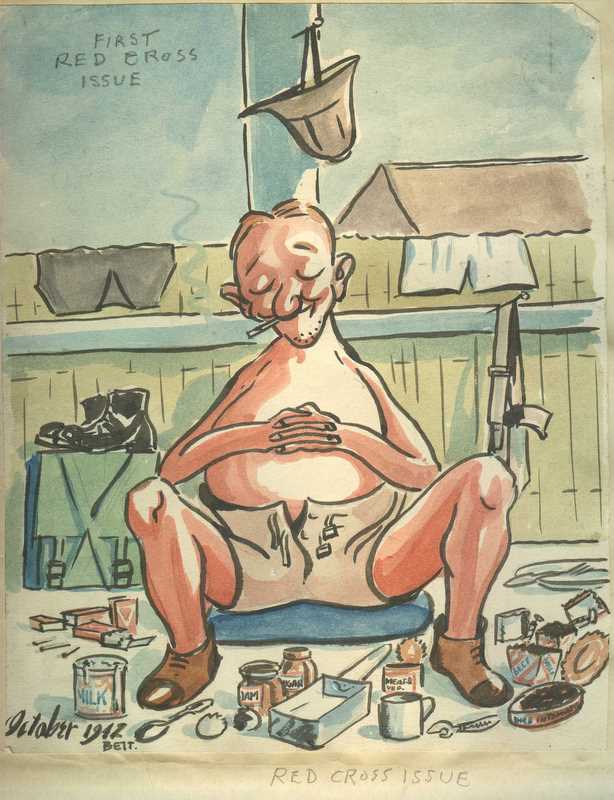

‘First Red Cross Issue’ (Oct 1942)

Another example of Des exaggerating what really didn’t occur in Changi at all, but trying to look on the funny side and the opposite extreme of what really occurred. Des seldom painted starving figures, as he told many ‘I painted to keep my sanity’. It seems clear that this must have been much need therapy for him. Details on what really occurred with Red Cross food issues follows.

The Japanese refused to allow Red Cross relief parcels to be distributed, so any supplementing of the meager rations depended on the ingenuity of the prisoners themselves.

‘The Red Cross was faced with enormous difficulties in getting to these camps and inspecting them. All too often the necessary documents needed for a visit were not issued and, as an example, the Japanese did not even tell the Red Cross how many POW camps they ran. The Red Cross were told by the Japanese that there were 42 POW camps when there were over 100. Getting any type of communication back to Britain was made all but impossible by the Japanese, so that families in Britain had no idea as to what was going on with regards to their loved ones in the Far East. The Red Cross received a degree of criticism for this after the war, but given the circumstances they found themselves in (their Borneo delegate and his wife were shot for trying to get a list of prisoner names off of the Japanese) such criticism was harsh.

During World War 2, the belligerent nations in Western Europe allowed the Red Cross to carry out its work of supporting those who had been taken prisoner. The same was not as true in the Pacific and Eastern European theatres of war. At the Changi camp run by the Japanese in Singapore, on average, a POW received a fraction of one food parcel sent by the Red Cross in the three-and-a half years that the camp was open. They also received just one letter per year. The Red Cross was linked to the Geneva Conventions on how captured personnel should be treated and Japan had not signed up to this.

In August 1942, the Japanese ordered that no neutral ship, even flying the flag of the Red Cross, would be allowed in Japanese waters. Clearly this meant that food parcels for POW’s held in Japan could not be sent. Food parcels were stockpiled in Vladivostok from September 1943 on, but they remained there until November 1944 when the Japanese allowed one ship to transport parcels to Japan. However, how much of this consignment actually got to POW’s or internees is not known. A second shipment never occurred as the ship was sunk.

The Japanese put a limit on the number of words a POW could receive in a letter. The maximum was 25 words that had to be typed in capital letters. Sending a letter from a POW camp was even more difficult as the Japanese had little time for POW’s who had surrendered. Such indifference meant that very little news came from the camps to families and the Red Cross could do little to change this.’

Source: http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/red_cross_and_world_war_two.htm

‘Condensed milk at 0.528 ounces per man was issued until the end of April 1942, and that was the last we saw of milk until the one Red Cross issue was made in October 1942.’

Source: Unknown Author, ‘Live to Eat’, in Lachlan Grant (ed.), The Changi Book, Published by New South in association with the Australian War Memorial, 2015, pg., 255

‘From March to August 1945 our new premises outside the gaol were not conducive to any activities other than work. There were some ten long wooden huts with thatched roofs, each holding about eighty men. Generally, because of the nature of the work, we got very dirty, and one of the few pleasures was showering at the end of the day’s activity. We were issued with some rather crude soap which was made in the gaol from fat and caustic soda. The couple of occasions when we were given soap from Red Cross parcels were indeed a great luxury.’

Source: You’ll Never Get Off The Island by Keith Wilson; 1989, Pg 106

‘Immediately after the war, Lady Mountbatten, in Red Cross uniform, wife of Lord Louis Mountbatten, Commander – in – Chief of our side of the Japanese war, tells how repeated requests for us to be allowed to receive Red Cross parcels, and to write and receive letters regularly, were flatly rejected by the Japanese government throughout our period of captivity. Also, now that they know how we were treated, and how many men died, those Japanese officers and officials who were responsible are being rounded up, to stand trial.’

Source: One Fourteenth of an Elephant, by Ian Denys Peek, 2005, Pg 488

Extracts from One Fourteenth of an Elephant by Ian Denys Peek reprinted by permission of Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd. Copyright © Ian Denys Peek 2003

‘The Red Cross had been sending pparcels into the camps and the Japanese had been storing them in the warehouses. Tons of Red Cross parcels were (now) released into camp (at capitulation).’

Source: The Battle for Singapore by Peter Thompson, pg 418